- I recommend the Pixel 9 to most people looking to upgrade - especially while it's $250 off

- Google's viral research assistant just got its own app - here's how it can help you

- Sony will give you a free 55-inch 4K TV right now - but this is the last day to qualify

- I've used virtually every Linux distro, but this one has a fresh perspective

- The 7 gadgets I never travel without (and why they make such a big difference)

5 Ways to Detect a Phishing Email: With Examples

Phishing is one of the most common types of cyber crime, but despite how much we think we know about scam emails, people still frequently fall victim.

According to Proofpoint’s 2022 State of the Phish Report, 83% of organisations fell victim to a phishing attack last year.

Meanwhile, Verizon’s 2021 Data Breach Investigations Report found that 25% of all data breaches involve phishing.

In this blog, we use real phishing email examples to demonstrate five clues to help you spot scams.

1. The message is sent from a public email domain

No legitimate organisation will send emails from an address that ends ‘@gmail.com’.

Not even Google.

Most organisations, except some small operations, will have their own email domain and company accounts. For example, legitimate emails from Google will read ‘@google.com’.

If the domain name (the bit after the @ symbol) matches the apparent sender of the email, the message is probably legitimate.

By contrast, if the email comes from an address that isn’t affiliated with the apparent sender, it’s almost certainly a scam.

The most obvious way to spot a bogus email is if the sender uses a public email domain, such as ‘@gmail.com’.

Image: Pickr

In this example, you can see that the sender’s email address doesn’t line up with the content of the message, which appears to be from PayPal.

However, the content of the message looks realistic, and the attacker has customised the sender’s name field so that it will appear in recipients’ inboxes as ‘Account Support’.

Other phishing emails will take a more sophisticated approach by including the organisation’s name in the local part of the domain. In this instance, the address might read ‘paypalsupport@gmail.com’.

At first glance, you might see the word ‘PayPal’ in the email address and assume that it was legitimate. However, you should remember that the important part of the address is what comes after the @ symbol. This dictates the organisation from which the email has come.

If the email is from ‘@gmail.com’ or another public domain, you can be sure that has come from a personal account.

Want to educate your staff on the threat of phishing?

Our Phishing Staff Awareness Training Programme contains everything your employees need to detect scam emails.

2. The domain name is misspelt

There’s another clue hidden in domain names that provide a strong indication of phishing scams – and it unfortunately complicates our previous clue.

The problem is that anyone can buy a domain name from a registrar. And although every domain name must be unique, there are plenty of ways to create addresses that are indistinguishable from the one that’s being spoofed.

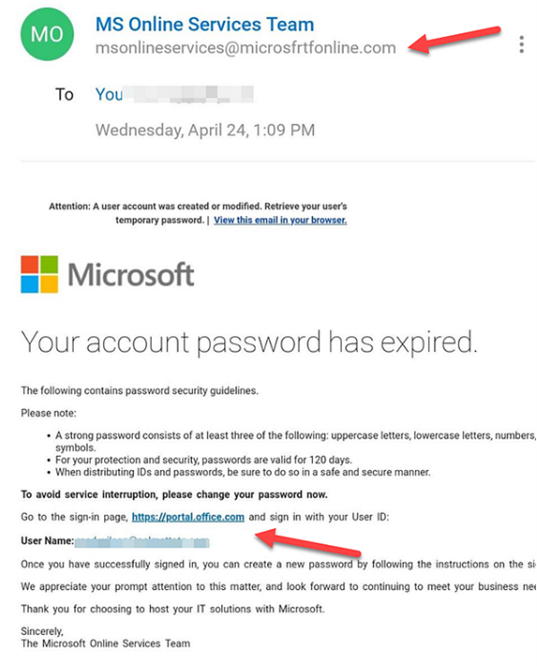

Take a look at this example:

Image: PTG

Here, scammers have registered the domain ‘microsfrtfonline.com’, which to a casual reader mimics the words ‘Microsoft Online’, which could reasonably be considered a legitimate address.

Meanwhile, some fraudsters get even more creative. The Gimlet Media podcast ‘Reply All’ demonstrated that in the episode What Kind Of Idiot Gets Phished?.

Phia Bennin, the show’s producer, hired an ethical hacker to phish various employees. He bought the domain ‘gimletrnedia.com’ (that’s r-n-e-d-i-a, rather than m-e-d-i-a) and impersonated Bennin.

His scam was so successful that he tricked the show’s hosts, Gimlet Media’s CEO and its president.

As Bennin went on to explain, you don’t even need to fall victim for a criminal hacker to gain vital information.

In this scam, the ethical hacker, Daniel Boteanu, could see when the link was clicked, and in one example that it had been opened multiple times on different devices.

He reasoned that the target’s curiosity kept bringing him back to the link but that he was suspicious enough not to follow its instructions.

Boteanu explains:

I’m guessing [the target] saw that something was going on and he started digging a bit deeper and […] trying to find out what happened […]

And I’m suspecting that after, [the target] maybe sent an email internally saying, “Hey guys! This is what I got. Just be careful. Don’t click on this […] email.

Boteanu’s theory is exactly what had happened. But why does that help the hacker? Bennin elaborates:

The reason Daniel had thought [the target] had done that is because he had sent the same email to a bunch of members of the team, and after [the target] looked at it for the fourth time, nobody else clicked on it.

And that’s okay for Daniel because he can try, like, all different methods of phishing the team, and he can try it a bunch of different times. [And] since [the target is] sounding alarm bells, he probably won’t include [him] in the next phishing attempt.

Therefore, in many ways, criminal hackers often still win even when you’ve thwarted their initial attempt.

That is to say, indecisiveness in spotting a phishing scam provides clues to the scammer about where the strengths and weaknesses in your organisation are.

It takes very little effort for them to launch subsequent scams that make use of this information, and they can keep doing this until they find someone who falls victim.

Remember, criminal hackers only require one mistake from one employee for their operation to be a success. As such, everyone in your organisations must be confident in their ability to spot a scam upon first seeing it.

3. The email is poorly written

You can often tell if an email is a scam if it contains poor spelling and grammar.

Many people will tell you that such errors are part of a ‘filtering system’ in which cyber criminals target only the most gullible people.

The theory is that, if someone ignores clues about the way the message is written, they’re less likely to pick up clues during the scammer’s endgame.

However, this only applies to outlandish schemes like the oft-mocked Nigerian prince scam, which you have to be incredibly naive to fall victim to.

That, and scams like it, are manually operated: once someone takes to the bait, the scammer has to reply. As such, it benefits the crooks to make sure the pool of respondents contains only those who might believe the rest of the con.

But this doesn’t apply to phishing.

See also:

With phishing, scammers don’t need to monitor inboxes and send tailored responses. They simply dump thousands of crafted messages on unsuspecting people.

As such, there’s no need to filter out potential respondents. Doing so reduces the pool of potential victims and helps those who didn’t fall victim to alert others to the scam, like we saw in the earlier example with Gimlet Media.

So why are so many phishing emails poorly written? The most obvious answer is that the scammers aren’t very good at writing.

Remember, many of them are from non-English-speaking countries and from backgrounds where they will have limited access or opportunity to learn the language.

With this in mind, it becomes a lot easier to spot the difference between a typo made by a legitimate sender and a scam.

When crafting phishing messages, scammers will often use a spellchecker or translation machine, which will give them all the right words but not necessarily in the proper context.

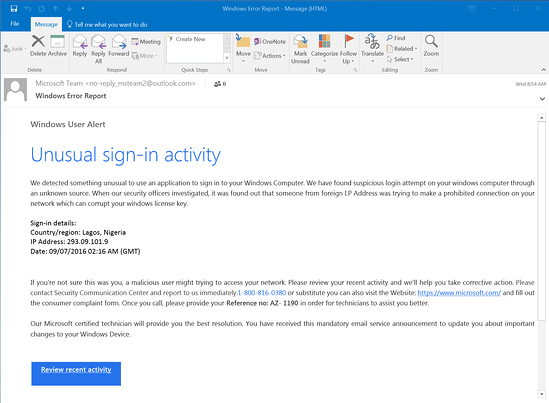

Take this example of a scam imitating Windows:

Image: KnowBe4

No individual word is spelled incorrectly, but the message is full of grammatical errors that a native speaker wouldn’t make, such as “We detected something unusual to use an application”.

Likewise, there are strings of missed words, such as in “a malicious user might trying to access” and “Please contact Security Communication Center”.

These are consistent with the kinds of mistakes people make when learning English. Any supposedly official message that’s written this way is almost certainly a scam.

That’s not to say any email with a mistake in it is a scam, however. Everyone makes typos from time to time, especially when they’re in a hurry.

It’s therefore the recipient’s responsibility to look at the context of the error and determine whether it’s a clue to something more sinister. You can do this by asking:

- Is it a common sign of a typo (like hitting an adjacent key)?

- Is it a mistake a native speaker shouldn’t make (grammatical incoherence, words used in the wrong context)?

- Is this email a template, which should have been crafted and copy-edited?

- Is it consistent with previous messages I’ve received from this person?

If you’re in any doubt, look for other clues that we’ve listed here or contact the sender using another line of communication, whether that’s in person, by phone, via their website, an alternative email address or through an instant message client.

4. It includes infected attachments or suspicious links

Phishing emails come in many forms. We’ve focused on emails in this article, but you might also get scam text messages, phone calls or social media posts.

But no matter how phishing emails are delivered, they all contain a payload. This will either be an infected attachment that you’re asked to download or a link to a bogus website.

The purpose of these payloads is to capture sensitive information, such as login credentials, credit card details, phone numbers and account numbers.

In this next section, we’ll explain how each of those works.

Infected attachments

An infected attachment is a seemingly benign document that contains malware. In a typical example, like the one below, the phisher claims to be sending an invoice:

Source: MailGuard

It doesn’t matter whether the recipient expects to receive an invoice from this person or not, because in most cases they won’t be sure what the message pertains to until they open the attachment.

When they open the attachment, they’ll see that the invoice isn’t intended for them, but it will be too late. The document unleashes malware on the victim’s computer, which could perform any number of nefarious activities.

We advise that you never open an attachment unless you are fully confident that the message is from a legitimate party. Even then, you should look out for anything suspicious in the attachment.

For example, if you receive a pop-up warning about the file’s legitimacy or the application asks you to adjust your settings, then don’t proceed.

Contact the sender through an alternative means of communication and ask them to verify that it’s legitimate.

Suspicious links

You can spot a suspicious link if the destination address doesn’t match the context of the rest of the email.

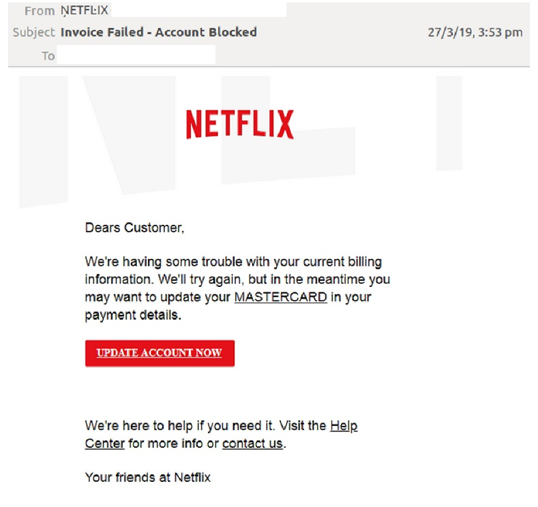

For example, if you receive an email from Netflix, you would expect the link to direct you towards an address that begins ‘netflix.com’.

Unfortunately, many legitimate and scam emails hide the destination address in a button, so it’s not immediately apparent where the link goes to.

Image: MailGuard

In this example, the scammers are claiming that there is an issue with the recipient’s Netflix subscription. The email is designed to direct them to a mock-up of Netflix’s website, where they will be prompted to enter their payment details.

By including the link within a button that says ‘Update account now’, the fraudsters achieve two thing. First, it makes the message look genuine, with buttons become increasingly popular in emails and website. But more importantly, it hides the destination address – making it instead a hyperlink.

To ensure you don’t fall for schemes like this, you must train yourself to check where links go before opening them.

Thankfully, this is straightforward: on a computer, hover your mouse over the link, and the destination address appears in a small bar along the bottom of the browser.

On a mobile device, hold down on the link and a pop-up will appear containing the link.

5. The message creates a sense of urgency

Scammers know that most of us procrastinate. We receive an email giving us important news, and we decide we’ll deal with it later.

But the longer you think about something, the more likely you are to notice things that don’t seem right.

Maybe you realise that the organisation doesn’t contact you by that email address, or you speak to a colleague and learn that they didn’t send you a document.

Even if you don’t get that ‘a-ha’ moment, coming back to the message with a fresh set of eyes might help reveal its true nature.

That’s why so many scams request that you act now or else it will be too late. This has been evident in every example we’ve used so far.

PayPal, Windows and Netflix all provide services that are regularly used, and any problems with those accounts could cause immediate inconveniences.

The manufactured sense of urgency is equally effective in workplace scams.

Criminals know that we’re likely to drop everything if our boss emails us with a vital request, especially when other senior colleagues are supposedly waiting on us.

A typical example looks like this:

Source: MailGuard

Phishing scams like this are particularly dangerous because, even if the recipient did suspect foul play, they might be too afraid to confront their boss.

After all, if they are wrong, they’re essentially implying that there was something unprofessional about the boss’s request.

However, organisations that value cyber security would accept that it’s better to be safe than sorry and perhaps even congratulate the employee for their caution.

Prevent phishing by educating your employees

To combat the threat of phishing, organisations must provide regular staff awareness training.

It’s only by reinforcing advice on avoiding scams that your team can develop good habits and detect malicious messages as second nature.

With our Phishing Staff Awareness Training Programme, these lessons are straightforward.

The online subscription course explains everything you need to know about phishing, and is updated each month to cover the latest scams.

A version of this blog was originally published on 16 March 2018.