- I recommend the Pixel 9 to most people looking to upgrade - especially while it's $250 off

- Google's viral research assistant just got its own app - here's how it can help you

- Sony will give you a free 55-inch 4K TV right now - but this is the last day to qualify

- I've used virtually every Linux distro, but this one has a fresh perspective

- The 7 gadgets I never travel without (and why they make such a big difference)

Google pushes .zip and .mov domains onto the Internet, and the Internet pushes back

Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

A recent move by Google to populate the Internet with eight new top-level domains is prompting concerns that two of the additions could be a boon to online scammers who trick people into clicking on malicious links.

Frequently abbreviated as TLD, a top-level domain is the rightmost segment of a domain name. In the early days of the Internet, they helped classify the purpose, geographic region, or operator of a given domain. The .com TLD, for instance, corresponded to sites run by commercial entities, .org was used for nonprofit organizations, .net for Internet or network entities, .edu for schools and universities, and so on. There are also country codes, such as .uk for the United Kingdom, .ng for Nigeria, and .fj for Fiji. One of the earliest Internet communities, The WELL, was reachable at www.well.sf.ca.us.

Since then, the organizations governing Internet domains have rolled out thousands of new TLDs. Two weeks ago, Google added eight new TLDs to the Internet, bringing the total number of TLDs to 1,480, according to the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, the governing body that oversees the DNS Root, IP addressing, and other Internet protocol resources.

Two of Google’s new TLDs—.zip and .mov—have sparked scorn in some security circles. While Google marketers say the aim is to designate “tying things together or moving really fast” and “moving pictures and whatever moves you,” respectively, these suffixes are already widely used to designate something altogether different. Specifically, .zip is an extension used in archive files that use a compression format known as zip. The format .mov, meanwhile, appears at the end of video files, usually when they were created in Apple’s QuickTime format.

Many security practitioners are warning that these two TLDs will cause confusion when they’re displayed in emails, on social media, and elsewhere. The reason is that many sites and software automatically convert strings like “arstechnica.com” or “mastodon.social” into a URL that, when clicked, leads a user to the corresponding domain. The worry is that emails and social media posts that refer to a file such as setup.zip or vacation.mov will automatically turn them into clickable links—and that scammers will seize on the ambiguity.

“Threat actors can easily register domain names that are likely to be used by other people to casually refer to file names,” Randy Pargman, director of threat detection at security firm Proofpoint, wrote in an email. “They can then use those conversations that the threat actor didn’t even have to initiate (or participate in) to lure people into clicking and downloading malicious content.”

Undoing years of anti-phishing and anti-deception awareness

A scammer with control of the domain photos.zip, for instance, could exploit the decades-long habit of people archiving a set of images inside a zip file and then sharing them in an email or on social media. Rather than rendering photos.zip as plaintext, which would have happened before Google’s move, many sites and apps are now converting them to a clickable domain. A user who thinks they are accessing a photo archive from someone they know could instead be taken to a website created by scammers.

Scammers “could easily set it up to deliver a zip file download whenever anyone visits the page and include any content they wish in the zip file, such as malware,” said Pargman.

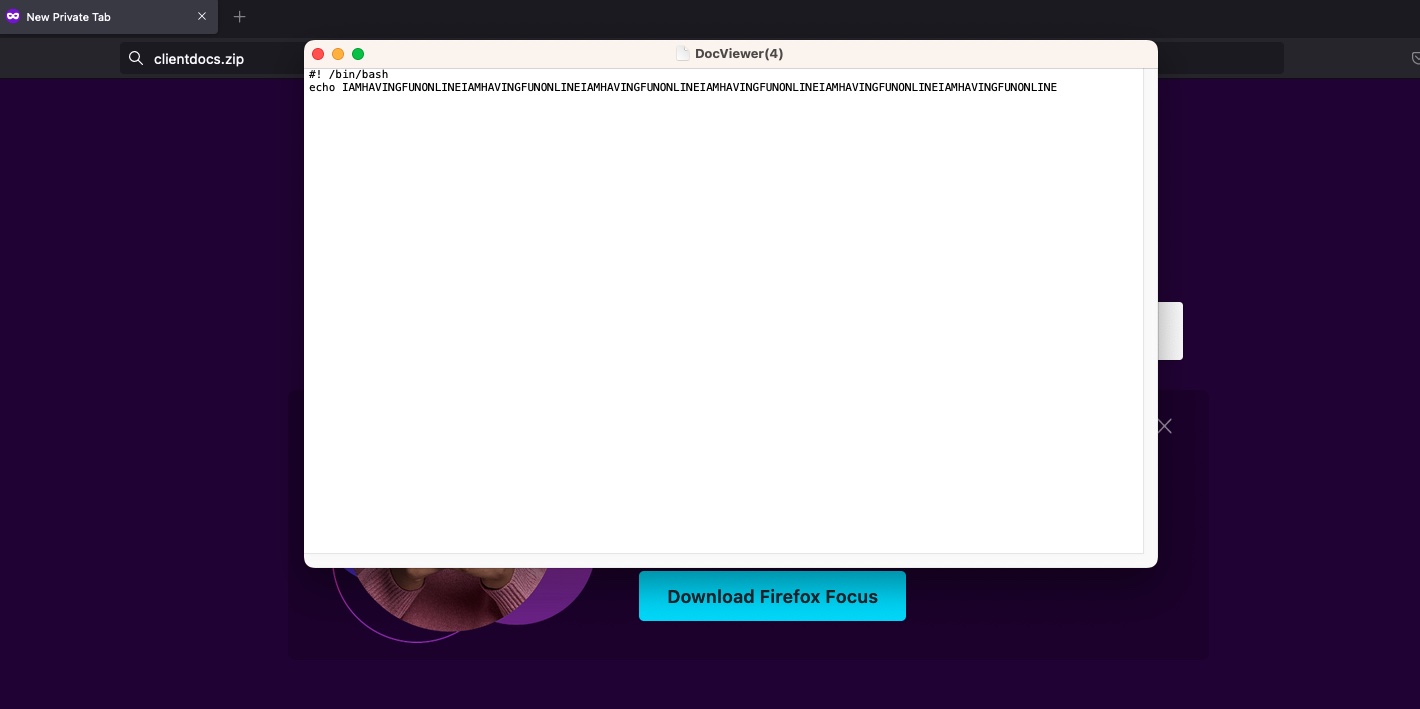

Several newly created sites demonstrate what this sleight of hand might look like. Among them are setup.zip and steaminstaller.zip, which use domain names that commonly refer to naming conventions for installer files. Especially poignant is clientdocs.zip, a site that automatically downloads a bash script that reads:

#! /bin/bash echo IAMHAVINGFUNONLINEIAMHAVINGFUNONLINEIAMHAVINGFUNONLINEIAMHAVINGFUNONLINEIAMHAVINGFUNONLINEIAMHAVINGFUNONLINE

It’s not hard to envision threat actors using this technique in ways that aren’t nearly as comical.

“The advantage for the threat actor is that they didn’t even have to send the messages to entice potential victims to click on the link—they just had to register the domain, set up the website to serve malicious content, and passively wait for people to accidentally create links to their content,” Pargman wrote. “The links seem much more trustworthy because they come in the context of messages or posts from a trusted sender.”