- How to install MacOS 26 on your MacBook (and which models support it)

- Everything announced at Apple's WWDC 2025 keynote: Liquid Glass, MacOS Tahoe, and more

- AI活用による保険代理店の変革―人材育成と業務効率化の新戦略とは?

- The FPGA turns 40. Where does it go from here?

- You can dismiss Apple Watch notifications with a flick of your wrist now

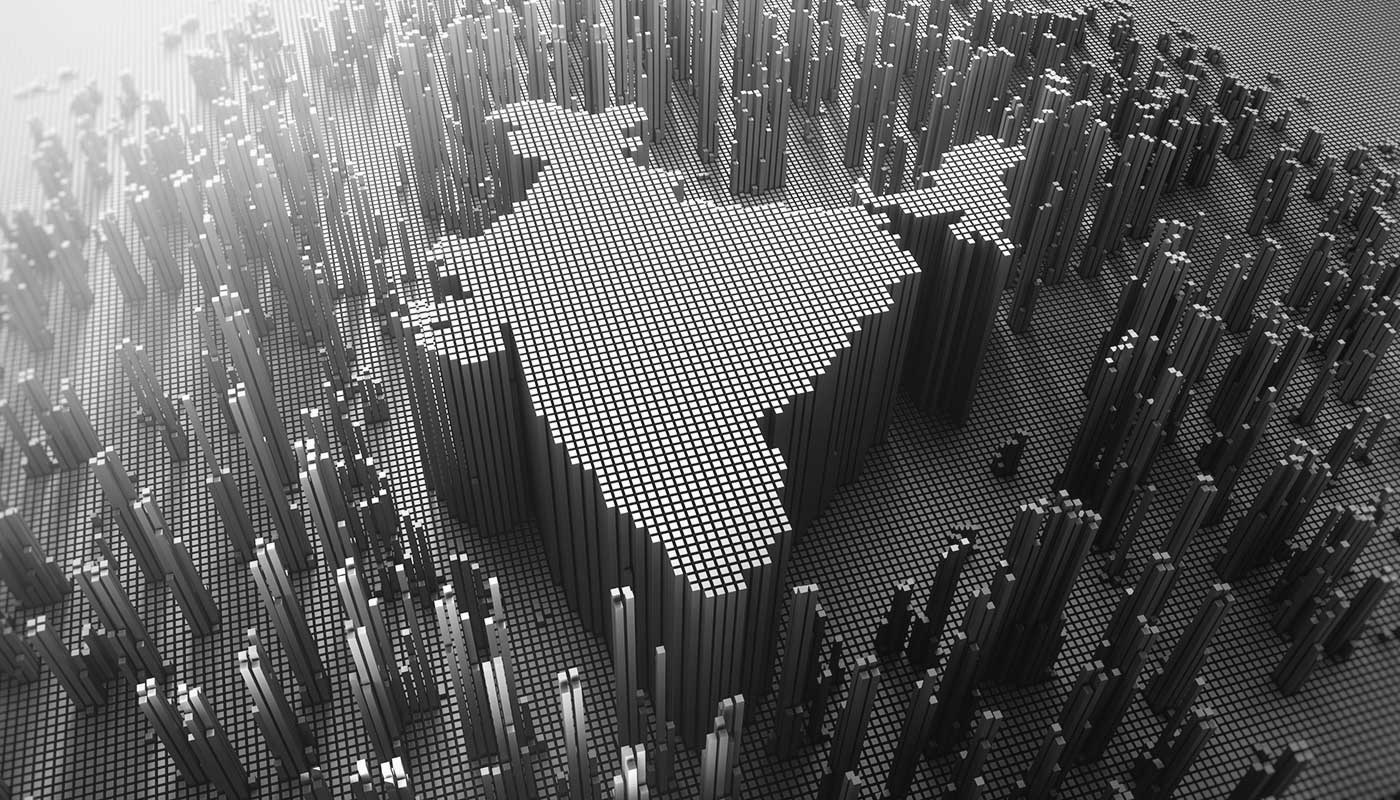

Understanding India’s Personal Data Protection Bill (PDPB)

Despite being the second-largest internet market in the world, India has yet to pass a comprehensive data privacy bill. It is important to have policies and regulations in place to protect them and their right to data privacy—a right that India’s Supreme Court recognized in 2017. Since then, the country’s government has been working towards passing a bill that codifies the rights of individuals to data privacy and protection. The most recent draft of the bill was released in late 2022, and it is expected to be tabled in Parliament during the Monsoon Session of July 2023. The following is a summary of the bill, its main points, its scope, and other pertinent information.

Scope and Goals of the Bill

The language of the bill states that it applies to “the processing of digital personal data within India where such data is collected online, or collected offline and is digitized” as well as “such processing outside India if it is for offering goods or services or profiling individuals in India.” Similar to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU, the bill is designed to protect the individuals within its purview, even when their data is processed by companies or other data fiduciaries outside of India. It also aims to strike a balance between individuals’ right to data privacy and the legitimate needs of data fiduciaries to process data.

Personal data is defined under the PDPB as “any data about an individual who is identifiable by or in relation to such data.” Because the bill only applies to digitized personal data, there are areas not covered, including anonymized data, non-digitized data, and non-personal data. The PDPB lays out the rights of the individuals under its protection, the regulations that data fiduciaries must comply with, and the legal recourse for noncompliance and the settling of grievances.

Provisions and Requirements Under the PDPB

The primary purpose of the bill is twofold, and the policies it outlines largely fall into two categories: the rights and responsibilities of data principals and those of data fiduciaries. Data principals are afforded several rights under the PDPB in regards to their data privacy. These include the right to information about what personal data of theirs is being processed and how, the right to withdraw consent for data to be processed, the right to correct and erase their personal data, the right to redress grievances through the data fiduciary or the Data Protection board, and the right to nominate an individual to act in their stead in the case that the data principal is unable to do so themselves.

Data principals are also subject to certain obligations: they must not register false reports or grievances, provide false information, suppress information, impersonate another individual, or give any false or fraudulent information in a request for data correction or erasure. By comparison, the obligations of data fiduciaries are many, as they must enable the principal to exercise their rights as well as fulfill other obligations for compliance. They are required to make data principals aware of what personal data is collected and why, obtain the principal’s informed consent and allow it to be withdrawn, and allow the correction and erasure of personal data.

In addition, data fiduciaries must work to ensure the data they process is accurate, employ security measures to protect personal data against breaches, erase data as soon as it is no longer needed, and notify the appropriate parties in the event of a data breach. Those fiduciaries classified as “significant data fiduciaries” (SDFs) are subject to further obligations, detailed later.

Comparing the PDPB and the GDPR

As the GDPR is relatively widely known and well-established, it may be useful to understand some of the policies laid out in the PDPB compared to similar provisions in the GDPR. While both account for the unique rights of minors to data privacy, the age of majority is 16 under the GDPR and 18 under the PDPB. The GDPR further classifies personal data into subsets such as data relating to race, ethnicity, politics, religion, and disability; certain categories are subject to different or stricter compliance laws than personal data in general. In contrast, India’s Bill addresses the general category of personal data, and no subset of data is more sensitive or protected than another.

On the subject of data fiduciaries, for which the EU’s equivalent is “data controllers,” the GDPR does not designate any further categories or special policies for certain subsets. The PDPB in India, on the other hand, classifies certain data fiduciaries as SDFs and requires them to comply with stricter regulations. These include appointing a data protection officer (DPO) to oversee grievance redressal, appointing an independent data auditor, and carrying out Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs).

Conclusion

While the PDPB has not yet been passed, it has been in the works and repeatedly revised for several years. The current version of the bill is a reflection of how much effort and debate went into it, and its passing would mean India having a comprehensive data privacy law in place to protect the more than 760 million active internet users in the country. Understanding the regulations and policies laid out in the PDPB is vital for any enterprise that processes personal data belonging to individuals in India, including many worldwide companies.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this guest author article are solely those of the contributor, and do not necessarily reflect those of Tripwire.