- Learn with Cisco at Cisco Live 2025 in San Diego

- This Eufy robot vacuum has a built-in handheld vac - and just hit its lowest price

- I highly recommend this Lenovo laptop, and it's nearly 50% off

- Disney+ and Hulu now offer prizes, freebies, and other perks to keep you subscribed

- This new YouTube Shorts feature lets you circle to search videos more easily

Block This Now: Cobalt Strike and Other Red-Team Tools

Application Security

,

Cybercrime

,

Cybercrime as-a-service

Attackers Keep Wielding Legitimate Tools and ‘Living Off the Land’ Tactics

Many attackers – highly skilled or otherwise – employ “living off the land” tactics, which means using legitimate tools or functionality already present in a network to target a victim. Accordingly, organizations need to do everything in their power to either block or at least closely monitor for such activity.

See Also: Frost & Sullivan Executive Brief: Beyond The Cloud

The trouble with detecting and blocking such attacks, which are launched by both criminal and nation-state hackers, is that they’re designed to look legitimate.

“Most modern security software should have process and file-access control that can be configured for tools like PowerShell, but a lot of organizations might not be aware of this.”

While such attacks are not new, they continue to bedevil organizations. In March, Microsoft warned that attackers were wielding Azure “LoLBins,” aka “living off the land binaries” with an extra helping of hacker lulz – which refers to weaponizing preinstalled, legitimate binaries built to run on Windows or Linux.

In September, a joint U.S. government alert warned attackers were using living-off-the-land tactics to exploit a vulnerability in Zoho’s single sign-on and password management tool.

Other types of living-off-the-land attacks continue to abound. One tool favored by both criminal hackers and nation-state attackers remains Cobalt Strike, which is a legitimate tool marketed by its makers as “software for adversary simulations and red team operations.” But attackers also use cracked copies of the tool to build botnets.

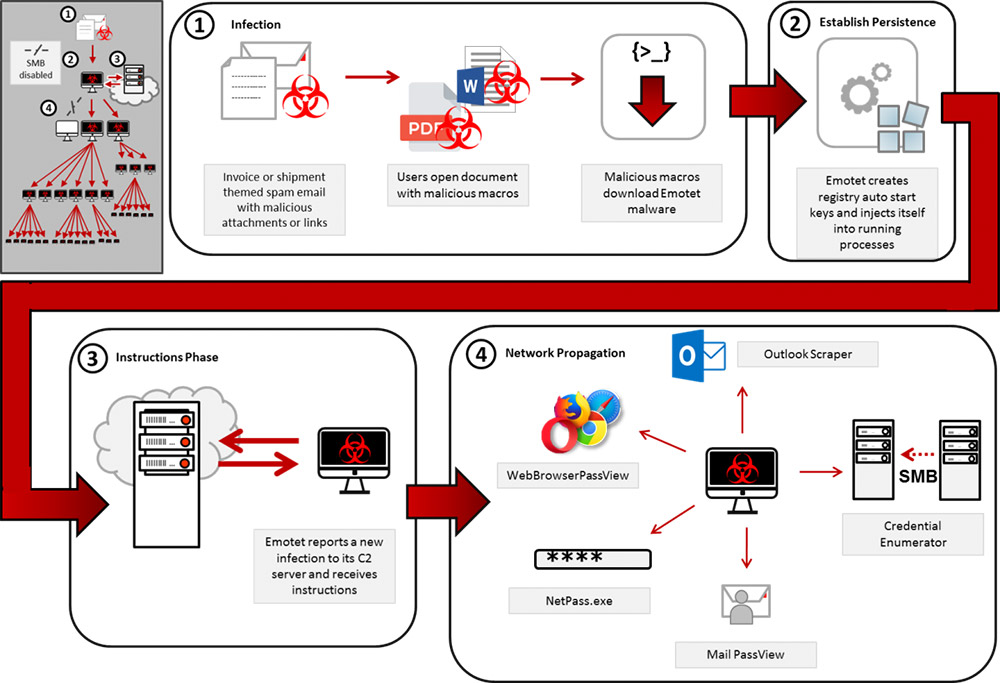

Earlier this month, security researchers warned that Emotet malware was pushing Cobalt Strike beacons directly onto infected endpoints, so attackers could more quickly evaluate the endpoint and see if they wished to escalate the attack, for example, by pushing ransomware onto the endpoint. Other attackers regularly use Cobalt Strike for “lateral movement,” meaning the endpoint becomes the beachhead in a lengthier attack, during which they’ll typically attempt to escalate privileges, access Active Directory Domain Controller, and use that to steal sensitive data, infect systems with crypto-locking malware and more.

Cobalt Strike employs a client/server approach and is based on a beacon, which is a payload that gets installed on a target system and that communicates with a command-and-control server via DNS, HTTP or HTTPS, according to a teardown published by European cybersecurity firm Sekoia. Beacons get controlled remotely by an administrator, using a Cobalt Strike client – aka the Aggressor – which connects to command-and-control Team servers that run on Linux OS.

By connecting to the Team server that manages a particular endpoint via its beacon, an administrator can remotely configure the beacon as well as receive “all information from the infected hosts,” Sekoia says.

“Cobalt Strike is unique in that its built-in capabilities enable it to be quickly deployed and operationalized regardless of actor sophistication or access to human or financial resources,” security firm Proofpoint said in a report released earlier this year.

How quick is quick? Earlier this month, threat intelligence firm Active Intelligence warned in the wake of the Log4j vulnerability becoming public knowledge that the Conti ransomware group appeared to be scanning for the vulnerability, using endpoints it had already infected with Cobalt Strike. In particular, Conti appeared to be attempting to exploit the Log4j functionality built into VMware vCenter server management software. A successful exploit, Advanced Intelligence warned, would give the attackers the ability to move laterally in a victim’s network.

‘Ban Hacking and Enumeration Tools’

The propensity of both criminals and nation-state attackers to employ Cobalt Strike for unhealthy purposes – not least in the SolarWinds supply chain attack – has led Bob McArdle, director of Trend Micro’s Forward-Looking Threat Research team in Europe, to dub Cobalt Strike “the Big Tobacco” of the cybersecurity field.

Given the risk posed by Cobalt Strike and its ilk, McArdle – in a presentation at last month’s Irish Reporting and Information Security Service conference IRISSCON in Dublin – recommended that all organizations “ban hacking and enumeration tools from the network,” including Cobalt Strike.

“In general for those tools – a lot of them fall into ‘dual usage,’ including PowerShell, PSExec, or even tools like AdFind,” McArdle tells me, referring to the powerful scripting language built into Windows (PowerShell), a lightweight replacement for telnet (PSExec), and a command line Active Directory query tool (AdFind).

How to Spot Such Tools

That doesn’t mean the use of these and other such tools – also including the Metasploit open-source penetration testing framework, Cobalt Strike, and other “potentially unwanted applications” – always goes unnoticed. But unless organizations are monitoring for such tools with an eye to their being used maliciously, alarm bells may not sound.

“A lot of security products detect them as Hacktool_ or PUA_ instead of more fully malicious ones like TROJ_,” McArdle says. “So it’s important for companies to be aware of this and to treat those sort of detections just as dangerously, especially when they’re running outside of any machines tagged as being in the admin group.”

In other words, in theory, detecting the malicious use of such tools isn’t difficult. But in practice, don’t expect such capabilities to be active by default.

“Most modern security software should have process and file-access control that can be configured for tools like PowerShell, but a lot of organizations might not be aware of this,” McArdle says. “A modern security suite does, after all, have a lot of options. So educating people to go look into those and enable them is a good first step.”