- Learn with Cisco at Cisco Live 2025 in San Diego

- This Eufy robot vacuum has a built-in handheld vac - and just hit its lowest price

- I highly recommend this Lenovo laptop, and it's nearly 50% off

- Disney+ and Hulu now offer prizes, freebies, and other perks to keep you subscribed

- This new YouTube Shorts feature lets you circle to search videos more easily

Criminals Use Malware to Steal Near Field Communication Data

Recent research by cybersecurity company ESET provides details about a new attack campaign targeting Android smartphone users.

The cyberattack, based on both a complex social engineering scheme and the use of a new Android malware, is capable of stealing users’ near field communication data to withdraw cash from NFC-enabled ATMs.

Constant technical improvements from the threat actor

As noted by ESET, the threat actor initially exploited progressive web app technology, which enables the installation of an app from any website outside of the Play Store. This technology can be used with supported browsers such as Chromium-based browsers on desktops or Firefox, Chrome, Edge, Opera, Safari, Orion, and Samsung Internet Browser.

PWAs, accessed directly via browsers, are flexible and do not generally suffer from compatibility problems. PWAs, once installed on systems, can be recognized by their icon, which displays an additional small browser icon.

Cybercriminals use PWAs to lead unsuspecting users to full-screen phishing websites to collect their credentials or credit card information.

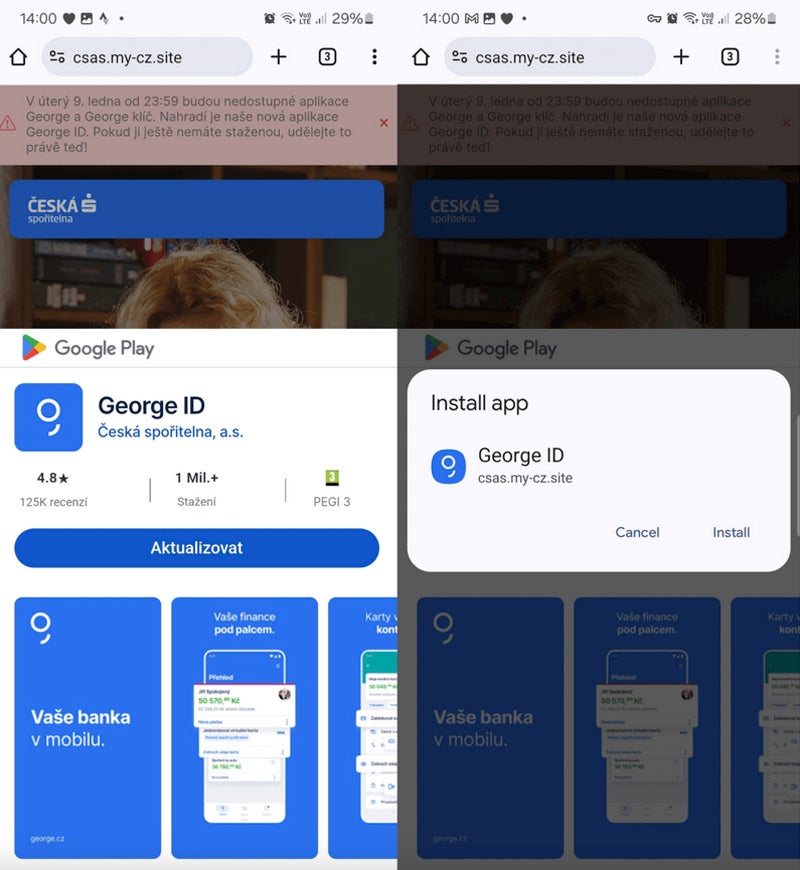

The threat actor involved in this campaign switched from PWAs to WebAPKs, a more advanced type of PWA. The difference is subtle: PWAs are apps built using web technologies, while WebAPKs use a technology to integrate PWAs as native Android applications.

From the attacker perspective, using WebAPKs is stealthier because their icons no longer display a small browser icon.

The victim downloads and installs a standalone app from a phishing website. That person does not request any additional permission to install the app from a third-party website.

Those fraudulent websites often mimic parts of the Google Play Store to bring confusion and make the user believe the installation actually comes from the Play Store while it actually comes directly from the fraudulent website.

NGate malware

On March 6, the same distribution domains used for the observed PWAs and WebAPKs phishing campaigns suddenly started spreading a new malware called NGate. Once installed and executed on the victim’s phone, it opens a fake website asking for the user’s banking information, which is sent to the threat actor.

Yet the malware also embedded a tool called NFCGate, a legitimate tool allowing the relaying of NFC data between two devices without the need for the device to be rooted.

Once the user has provided banking information, that person receives a request to activate the NFC feature from their smartphone and to place their credit card against the back of their smartphone until the app successfully recognizes the card.

Full social engineering

While activating NFC for an app and having a payment card recognized may initially seem suspicious, the social engineering techniques deployed by threat actors explain the scenario.

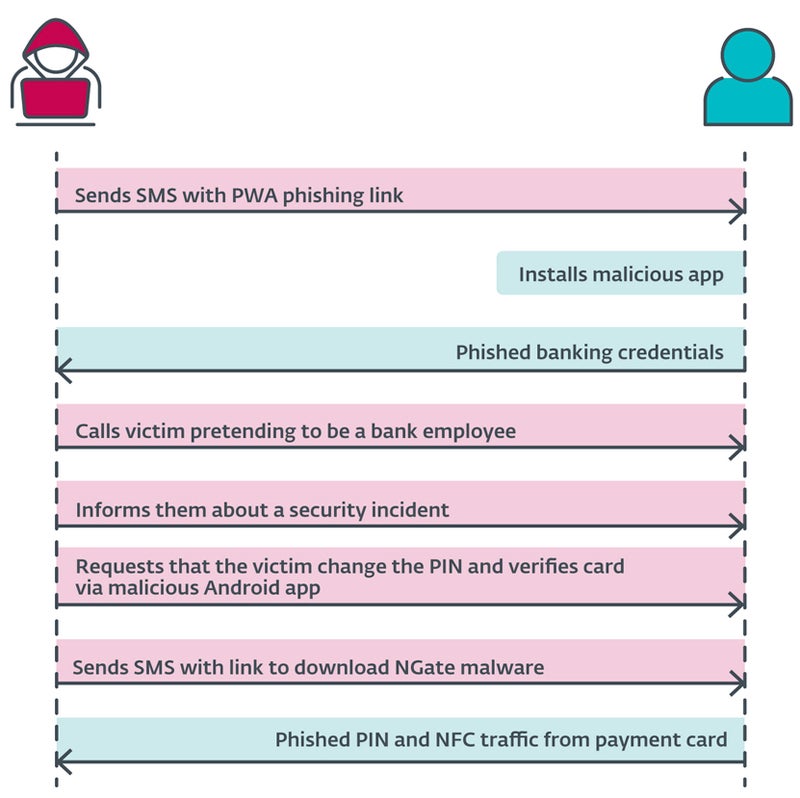

The cybercriminal sends a SMS message to the user, mentioning a tax return and including a link to a phishing website that impersonates banking companies and leads to a malicious PWA. Once installed and executed, the app requests banking credentials from the user.

At this point, the threat actor calls the user, impersonating the banking company. The victim is informed that their account has been compromised, likely due to the previous SMS. The user is then prompted to change their PIN and verify banking card details using a mobile application to protect their banking account.

The user then receives a new SMS with a link to the NGate malware application.

Once installed, the app requests the activation of the NFC feature and the recognition of the credit card by pressing it against the back of the smartphone. The data is sent to the attacker in real time.

Monetizing the stolen information

The information stolen by the attacker allows for usual fraud: withdrawing funds from the banking account or using credit card information to buy goods online.

However, the NFC data stolen by the cyberattacker allows them to emulate the original credit card and withdraw money from ATMs that use NFC, representing a previously unreported attack vector.

Attack scope

The research from ESET revealed attacks in the Czech Republic, as only banking companies in that country were targeted.

A 22-year old suspect has been arrested in Prague. He was holding about €6,000 ($6,500 USD). According to the Czech Police, that money was the result of theft from the last three victims, suggesting that the threat actor stole much more during this attack campaign.

However, as written by ESET researchers, “the possibility of its expansion into other regions or countries cannot be ruled out.”

More cybercriminals will likely use similar techniques in the near future to steal money via NFC, especially as NFC becomes increasingly popular for developers.

How to protect from this threat

To avoid falling victim to this cyber campaign, users should:

- Verify the source of the applications they download and carefully examine URLs to ensure their legitimacy.

- Avoid downloading software outside of official sources, such as the Google Play Store.

- Steer clear of sharing their payment card PIN code. No banking company will ever ask for this information.

- Use digital versions of the traditional physical cards, as these virtual cards are stored securely on the device and can be protected by additional security measures such as biometric authentication.

- Install security software on mobile devices to detect malware and unwanted applications on the phone.

Users should also deactivate NFC on smartphones when not used, which protects them from additional data theft. Attackers can read card data through unattended purses, wallets, and backpacks in public places. They can use the data for small contactless payments. Protective cases can also be used to create an efficient barrier to unwanted scans.

If any doubt should arise in case of a banking company employee calling, hang up and call the usual banking company contact, preferably via another phone.

Disclosure: I work for Trend Micro, but the views expressed in this article are mine.