- Enterprises face data center power design challenges

- #Infosec2025: Channel Bridges Security Skills Gap

- Need to relax? These sound apps do the trick for me - here's how

- Educating Tomorrow's Tech Workforce: A New Map for AI-Era Skills

- A year after testing, these Nothing earbuds are still my favorite I've used

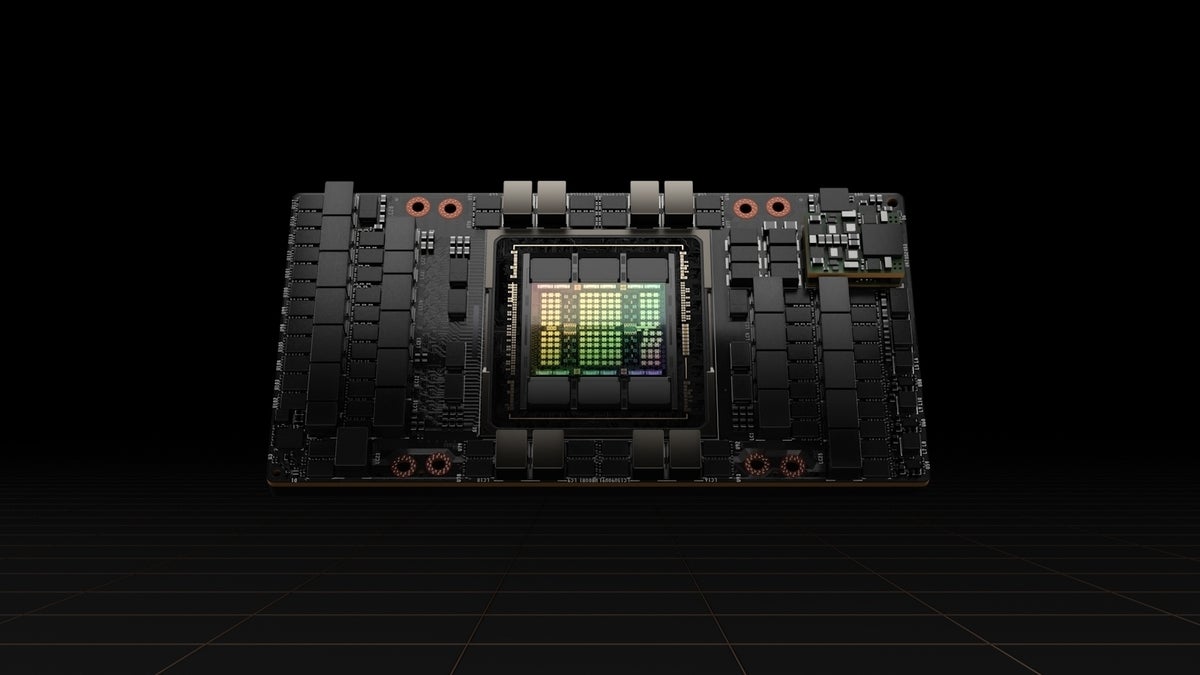

Nvidia still crushing the data center market

Nvidia is playing some serious games.

When Jensen Huang and his two partners established Nvidia in 1993, the graphics chip market had many more competitors than the CPU market, which had just two. Nvidia’s competitors in the gaming market included ATI Technologies, Matrox, S3, Chips & Technology, and 3DFX.

A decade later, Nvidia had laid waste to every one of them except for ATI, which was purchased by AMD in 2006. For most of this century, Nvidia has shifted its focus to bring the same technology it uses to render videogames in 4k pixel resolution to power supercomputers, high-performance computing (HPC) in the enterprise, and artificial intelligence.

The results of that shift are laid clear in Nvidia’s financial reports and in the industry. For its most recent quarter, data center revenue hit $3.81 billion, up 61% from a year earlier, and it accounted for 56% of Nvidia’s total revenue. In the latest Top500 list of supercomputers, 153 are running Nvidia accelerators while AMD only has nine. According to IDC, Nvidia held 91.4% of the enterprise GPU market to AMD’s 8.5% in 2021.

How did it get here? Earlier in the century, Nvidia realized that the nature of the GPU, a floating-point math co-processor with thousands of cores running in parallel, lends itself very well to HPC and AI computing. Like 3D graphics, HPC and AI are heavily dependent on floating-point math.

The first steps toward an enterprise shift came in 2007, when former Stanford University computer science professor Ian Buck developed CUDA, a C++-like language for programming GPUs. Videogame developers didn’t code to the GPU; they programmed to Microsoft’s DirectX graphics library, which in turn spoke to the GPU. CUDA presented an opportunity to code directly to the GPU just like a programmer working in C/C++ would to a CPU.

Fifteen years later, CUDA is taught in several hundred universities around the world and Buck is the head of Nvidia’s AI efforts. CUDA allowed developers to make GPU-specific applications – something not doable before –but it also locked them into the Nvidia platform, because CUDA is not easily portable.

Few companies play in both the consumer and enterprise spaces. Hewlett-Packard split itself in two to better serve those markets. Manuvir Das, vice president of enterprise computing at Nvidia, says the company “is definitely focused on enterprise companies today. Of course, we’re also a gaming company entity. That’s not going to change.”

The gaming and enterprise sides of the house both use the same GPU architecture, but the company thinks of these two businesses as separate entities. “So in that sense, we’re almost sort of two companies within one. It’s one architecture but two very different routes to market, sets of customers, use cases, all of that,” he says.

Das adds that Nvidia has a range of GPUs, and they all have different functionality depending on the target market. The enterprise GPUs have a transformer engine that performs natural language processing, for example, and other functions which are not found in the gaming GPUs.

Addison Snell, principal researcher and CEO of Intersect360 Research, says Nvidia is straddling the two markets well for now. However, “the growth in GPU computing is really taking them full force into enterprise computing and AI. And I think they’re predominantly now serving the hyperscale market there, which is the home of the majority of AI spending,” Snell says.

Anshel Sag, principal analyst with Moor Insights & Strategy, echoes this. “I feel like a lot of the company’s efforts are very much focused on the enterprise today, but I still think that there’s a lot of gaming that’s still very much within its overall branding,” he says.

Sag believes Nvidia’s biggest room for improvement is in mobile technologies, where it plays second fiddle to Qualcomm. “I think they’re very weak in the mobile space, and that mobile space is not just limited to smartphones, but handheld gaming, and AR/VR applications. I think it exposes them on the edge, and I think that they will have competition down the road,” Sag says.

According to Snell, Nvidia is continuing to downplay HPC in favor of AI and focusing on hyperscale companies, counting on cloud computing as the delivery mechanism for all types of enterprise computing.

“This points to Nvidia aiming to be a complete solution provider for hyperscale and cloud, while diminishing its efforts as a component provider through traditional server OEMs to end users,” Snell says.

Competing against its partners

Nvidia operates differently than other chip giants in that it competes with its OEM partners. That has caused at least one public blowup.

In September, peripheral maker EVGA announced it would no longer make Nvidia cards. EVGA was one of the top vendors in the market, and graphics cards accounted for 80% of its income. So they had to be pretty angry with Nvidia to walk away from 80% of its revenue.

EVGA CEO Andy Han cited several grievances with Nvidia, not the least of which was that it competes with Nvidia. Nvidia makes graphics cards and sells them to consumers under the brand name Founder’s Edition, something AMD and Intel do very little or not at all.

In addition, Nvidia’s line of graphics cards was being sold for less than what licensees were selling their cards. So not only was Nvidia competing with its licensees, but it was also undercutting them.

Nvidia does the same on the enterprise side, selling DGX server units (rack-mounted servers packed with eight A100 GPUs) in competition with OEM partners like HPE and Supermicro. Das defends this practice.

“DGX for us has always been sort of the AI innovation vehicle where we do a lot of item testing,” he says, adding that building the DGX servers gives Nvidia the chance to shake out the bugs in the system, knowledge it passes on to OEMs. “Our work with DGX gives the OEMs a big head-start in getting their systems ready and out there. So it’s actually an enabler for them.”

But both Snell and Sag think Nvidia should not be competing against its partners. “I’m highly skeptical of that strategy,” Snell says. “It defies the tenet of not competing with your own customers. If I were one of the major server OEMs, I wouldn’t like the idea that Nvidia is now acting as a system provider and taking me out of the loop.”

“I think those [DGX] systems do, to a certain degree, compete with what their partners are offering. But that said, I also think that Nvidia doesn’t necessarily want to provide support and services for those systems, like their partners will. And I think that’s a big component of the enterprise solutions that isn’t really present on the consumer side,” Sag says.

AMD, Intel bolster their GPU technologies

So who might knock Nvidia from its perch? Throughout the history of the Silicon Valley, most companies that experienced a great fall were not knocked off by a competitor but fell apart from within.

IBM and Apple in the 1990s, Sun Microsystems, SGI, Novell, and now Facebook were all undone or nearly undone because of bad management and bad decisions, not because somebody else came along and knocked them off.

Nvidia has had product misfires along the way, but it has always quickly course-corrected with the next generation of silicon. And it has had pretty much the same executive management team since the beginning, and they haven’t made that many mistakes.

One thing that helped Nvidia achieve such dominance is that it had the market to itself. AMD was struggling to survive for years, and Intel repeatedly tried and failed to develop a GPU.

But that’s not the case anymore. AMD is thoroughly revitalized, and it has bragging rights now that its GPU technology, Instinct, is powering the fastest supercomputer in the world, Frontier. And Intel finally seems to be on the right track with its Xe GPU architecture, found in the forthcoming Ponte Vecchio enterprise GPU.

If there’s a company that has Das looking over his shoulder, he isn’t admitting it, however. “I think the real competition we see is basically how do we [support] the workloads that already exist, that are running non-accelerated?” he asks.

Copyright © 2022 IDG Communications, Inc.