- Apple doesn't need better AI as much as AI needs Apple to bring its A-game

- I tested a Pixel Tablet without any Google apps, and it's more private than even my iPad

- My search for the best MacBook docking station is over. This one can power it all

- This $500 Motorola proves you don't need to spend more on flagship phones

- Finally, budget wireless earbuds that I wouldn't mind putting my AirPods away for

TrickGate crypter discovered after 6 years of infections

New research from Check Point Research exposes a crypter that stayed undetected for six years and is responsible for several major malware infections around the globe.

In new research, Check Point has exposed a crypter dubbed TrickGate developed by cybercriminals and sold as a service.

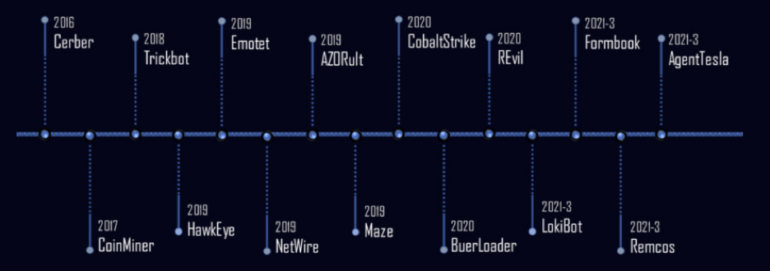

The crypter has been in development since 2016 when it was used to spread the Cerber malware, but it has been used for several major malware campaigns, including Trickbot and Emotet (Figure A).

Figure A

Jump to:

TrickGate’s massive distribution

Check Point monitored 40 to 650 attacks per week over the last two years and found the most popular malware family crypted by TrickGate was FormBook, an information stealer malware.

The threats crypted by TrickGate are delivered in different formats depending on the threat actor deploying it. All the usual initial compromise vectors can be used, such as phishing emails or abuse of vulnerabilities to compromise a server or computer, and the crypted files might be in archive files (ZIP, 7 ZIP or RAR) or in the PDF or XLSX format.

SEE: Mobile device security policy (TechRepublic Premium)

How did TrickGate stay undetected for so long?

Security researchers considered parts of the TrickGate code to be shared code that would be widely used by many cybercriminals, as is often the case in the malware development environment where developers often copy existing code from others and modify it.

When Check Point suddenly stopped seeing that code being used, they discovered that it had stopped deploying for several different attack campaigns at the exact same time. As it’s unlikely that different threat actors took vacation at the same time, the researchers dug further and found TrickGate.

TrickGate’s functionalities

Although the code analyzed by the researchers has changed over the last six years, the main functionalities exist on all samples.

It uses the API hash resolving technique to hide the names of the Windows APIs strings as they are turned into a hash number. It then adds unrelated clean code and debug strings inside the crypted file in order to raise false flags for the analysts and render the analysis harder.

TrickGate always changes the way the payload is decrypted so that automated unpacking for another version is useless. Once the payload is decrypted, it is injected in a new process by a set of direct calls to the kernel.

What can be done against the TrickGate threat?

The crypter/packer problem has been around for many years. As Check Point stated in the report: “Packers often get less attention, as researchers tend to focus their attention on the actual malware, leaving the packer stub untouched.”

Reverse engineers working on improving malware detection often focus on the malware itself because it can be packed or crypted with any crypter tool and it’s important to detect the final payload, which is the most malicious component of the attack.

Ideally, packer/crypter code should be considered the same as malware and raise alarms, but what makes it a difficult task is that legitimate packers do exist and should not be blocked.

Security solutions need to implement specific detections for crypters that are known to be malicious. Those detections are difficult to maintain as they need to be updated every time the crypter evolves.

Crypters render automated static analysis useless, as analysis tools will only see the crypter code and not the final payload. It is strongly advised to adopt security solutions that have the capability to do dynamic and behavior analysis, such as sandboxes, as those solutions will be able to monitor the whole code flow from the depacking to the delivery of the final payload and its execution.

Disclosure: I work for Trend Micro, but the views expressed in this article are mine.