- I recommend the Pixel 9 to most people looking to upgrade - especially while it's $250 off

- Google's viral research assistant just got its own app - here's how it can help you

- Sony will give you a free 55-inch 4K TV right now - but this is the last day to qualify

- I've used virtually every Linux distro, but this one has a fresh perspective

- The 7 gadgets I never travel without (and why they make such a big difference)

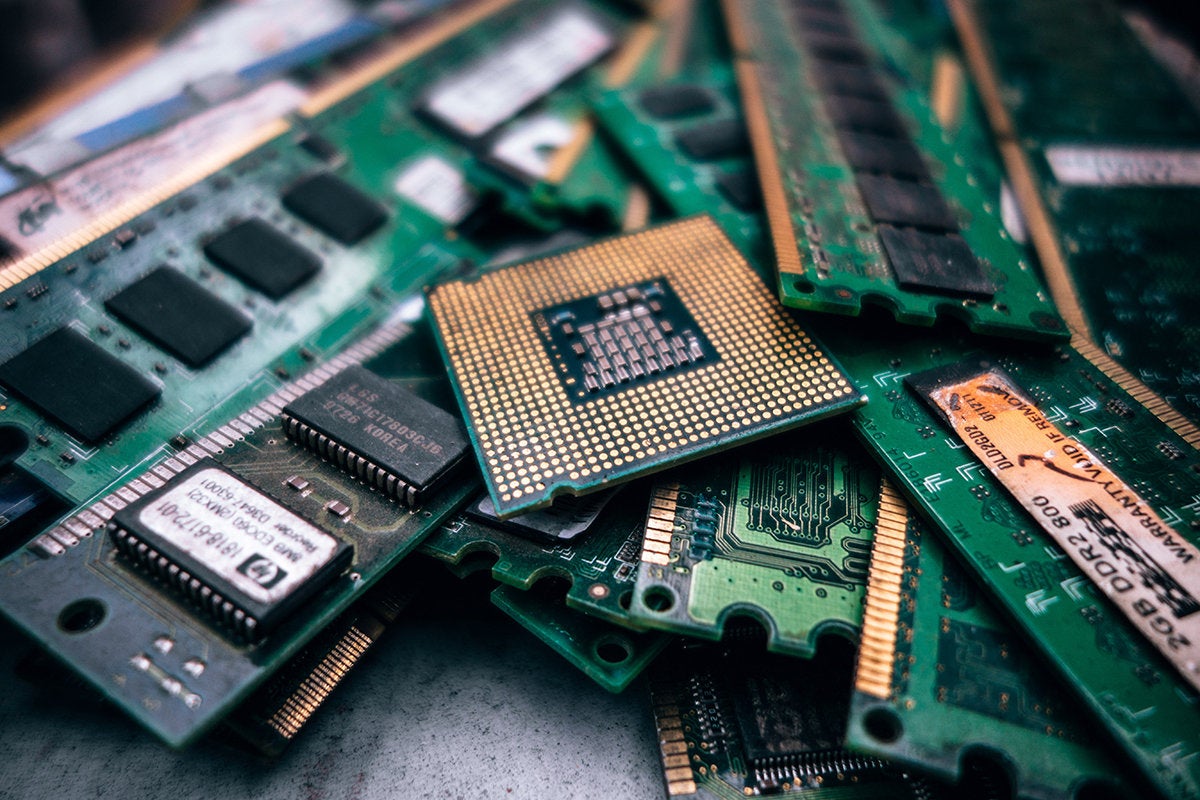

US-China chip war puts global enterprises in the crosshairs

As the US-China trade war escalates, with President Joe Biden’s administration issuing sweeping restrictions on exports of chip technology, enterprises in different economic sectors worldwide are bound to get caught in the crossfire between the world’s two largest economies.

The new trade rules come at a time when the US is getting increasingly worried about China’s growing geopolitical power, and will affect not only computer equipment, but many consumer products built on the restricted semiconductor technology. They also signal the end of the era of ever-expanding globalization.

Enterprises of all stripes will have to analyze their supply chains to determine how they may be affected, experts say.

“A fully rationalized global value chain is where basically capital and expertise and production migrates to its most efficient point. Those days are over for any strategic goods, not just semiconductors but anything that is strategic,” said Alex Capri, research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation, a global trade research organization.

In early October, the Biden administration issued new export controls that block US companies from selling advanced semiconductors as well as equipment used to make them to certain Chinese manufacturers unless they receive a special license.

Then in mid-December, the administration expanded those restrictions to include 36 additional Chinese chip makers from accessing US chip technology, including Yangtze Memory Technologies Corporation (YMTC), the largest contract chip maker in the world.

Perhaps most importantly, the export controls include restrictions on semiconductors used in AI, such as GPUs (graphical processing units), TPUs (tensor processing units), and other advanced ASICs (application-specific integrated circuits).

The stated purpose of the restrictions is to deny China access to advanced technology for military modernization and human rights abuses. The restrictions may be lifted on a case-by-case basis if the US is able to verify that the Chinese companies on the restricted list are not using technology for military purposes or to curtail human rights.

US chip export rules already have an impact

Meanwhile, the export rules are already having an impact. Apple, for example, was planning to work with YMTC for iPhone 14’s flash memory. Apple had already completed a month-long process of certifying the company as its supplier before the Biden administration launched its offensive against Chinese chipmakers.

Other big companies immediately affected by the restrictions include Nvidia and AMD, which make GPUs and do business with Chinese companies. Other chip makers are affected as well, since the rules cover a range of semiconductors over certain power specifications.

It’s not just the US chipmakers who are directly impacted by the restrictions, however. The new rules also prohibit US businesses from trade with non-US companies exporting the restricted technology to China. This has caused friction with the US and some of its allies, but most companies affected by the rules globally appear to be ready to adhere to them.

As a result, Dutch semiconductor equipment maker ASML will now be unable to serve one of its largest markets. Similarly, UK chip design firm ARM recently announced it won’t sell its high performance chip technology to China.

The result is that a range of leading Chinese tech vendors like e-commerce giant Alibaba, intenet services company Baidu, networking powerhouse Huawei, and AI firms SenseTime and Megvii, will struggle to source advanced chips to run their artificial intelligence workloads, said Josep Bori, research director for thematic intelligence at analytics and consulting company GlobalData.

“They won’t be able to buy them from Nvidia or AMD any longer, and Chinese AI chip vendors like HiSilicon, Cambricon, Horizon Robotics or Biren Technology will not be able to manufacture their own AI chips because foundries like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) are also obeying the US ban and the Chinese foundries (mainly SMIC) are not yet capable of manufacturing anything smaller than 14 nanometers,” Bori said.

Meanwhile, non-Chinese companies have already started shifting manufacturing capacity out of China, with TSMC setting up manufacturing plants in US and Europe, and Apple’s largest supplier, Foxconn, rapidly trying to scale its iPhone manufacturing in India. However, such factories take several years to build, and in the meantime, experts believe there will be phases of disruptions and shortages and uncertainties in global supply chains.

The restrictions imposed by the Biden administration will have a more significant effect than prior US trade bans, with disruptions felt far and wide, experts said.

Chip war will affect variety of products

“In addition to the chipmakers and semiconductor manufacturers in China, every company on the supply chain of advanced chipsets, such as the electronic vehicle manufacturers and HPC [high performance computing] makers in China, will be hit,” said Charlie Dai, research director at market research firm Forrester. “There will also be collateral damage to the global technology ecosystem in every area, such as the chip design, tooling, and raw materials.”

Enterprises might not feel the burn right away, since interdependencies between China and the US will be hard to unwind immediately. For example, succumbing to pressure from US businesses, in early December the US Department of Defense said it would allow its contractors to use chips from the banned Chinese chipmakers until 2028.

In addition, the restrictions are not likely to have a direct effect on the ability of the global chip makers to manufacture semiconductors, since they have not been investing in China to manufacture chips there, said Pareekh Jain, CEO at Pareekh Consulting.

The new rules, though, will have knock-on effects for chip makers and other manufacturers.

“China, being the world’s second-largest economy, is a huge market for many global semiconductor enterprises and it will impact their revenue and growth plans,” Jain said. ” They might scale down their chip-making production plans, which require heavy investment, because of cash flow issues in short term. In the long term, it will accelerate more local chip-making in India, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore and other countries.”

Nations bolster chip manufacturing capabilities

Taiwan has for long maintained a lead in manufacturing semiconductor chips that go into PCs, servers, and equipment used for advanced research. However, now several countries, including India, France, UK, Japan and even Australia are rolling out incentives to attract semiconductor investments.

The trade restrictions are likely to cause other long-term changes in global manufacturing and trade .

“These sanctions will encourage more manufacturing investment in the production of phones, cars, electronics, other white goods, machines, telecom equipment, etc., outside China including India, Vietnam, and other countries,” Jain said. “Currently, this manufacturing shift was happening because of local market in India and diversification strategy to mitigate supply chain disruptions. But chip restrictions will act as an incentive to boost export manufacturing also from India and other countries.”

Meanwhile, the US Congress approved the CHIPS Act—legislation that earmarks billions of dollars in subsidies for companies building chip fabs in the country. China too is pouring in $143 billion to boost its domestic chip manufacturing in the face of the trade restrictions.

TSMC founder Morris Chang recently warned that globalization is “almost dead,” with many countries trying to set up their own semiconductor fabrication plants. While this may sound like a good strategic move by various governments, excess capacity—as seen in the past—could lead to viability issues for chipmakers, possibly resulting in another supply chain havoc in the global market.

CIOs need to reassess their supply chains

While most enterprises may not be directly dealing with Chinese entities impacted by the ban, the wide scope of the ban means they will need to thoroughly assess their entire technology supply chain for any possible linkages.

“I think that if you are a CIO in a company working in artificial intelligence projects, be it to automate your production lines or to provide automatic assistance to your customers or what have you, then you may want to carefully consider your suppliers,” Bori said. “If any is Chinese, you may suffer disruption (now or when further regulations are enacted). For instance, if you’re using Alibaba cloud for your AI training workloads. Or if you were sourcing AI accelerator chips from Horizon Robotics.”

Even if an enterprise is not working or planning to work on an AI project that may require such chips, the fluidity of the situation calls for technology professionals to work on their supply chain resiliency program, pointed out Singapore-based Foong King Yew, an analyst at Third Eye Advisory.

“CIOs need to reassess their vendor selection criteria from the standpoint of supply chain resiliency—i.e., how exposed it is to the China semiconductor chip problem. They need to identify potential vulnerabilities in high-tech projects including enterprise high performance computing etc and assess the capabilities of such vendors in terms of future upgrades, technology roadmap, and support capabilities,” Foong said.

Important questions that need to be addressed are whether Chinese vendors in your supply chain will be able to provide the same levels of technology and support in the future if they have problems accessing advanced chips or technology from their Western partners. “If such vendors are restricted to using of old chips, these may affect technical performance,” Foong said.

Copyright © 2022 IDG Communications, Inc.